The results of this experiment are not exactly close to my target as you can see, but I thought it was worth a blog post anyway. There was this rough idea I've been thinking about in Conway's Game of Life for a really long time.

I wonder if it's possible to use some kind of stochastic algorithm that gives you an initial state which forms legible text after many cycles.

— yakinavault (@yakinavault) August 7, 2020

I came across an article of the same title by Kevin Galligan recently and I thought I could do something similar using a different approach. What if instead of using SAT Solvers, I use some kind of heuristic algorithm that could somehow "program" a large world of Game of Life to display an image after a few generations?

There are other ways of achieving this. One is by placing still life states at specific pixels as described in this codegolf question.

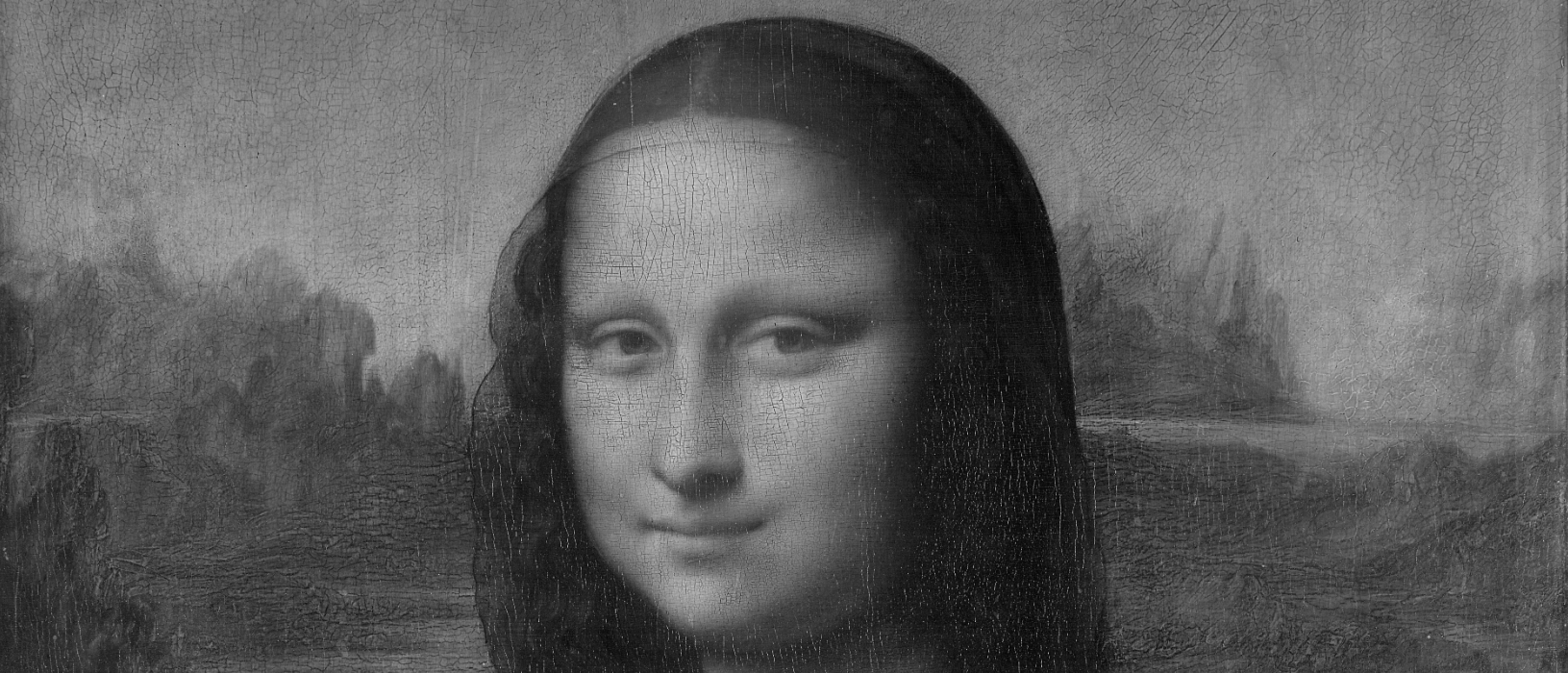

What I'm thinking of is to display Mona Lisa for a single frame/generation of 'non-still' Game of Life.

Algorithm

I began working on a proof of concept using the hill climbing algorithm. The idea was very simple. Iteratively modify a random 2D Game of Life state until it's Nth generation looks similar to Mona Lisa. Here's the full algorithm.

best_score := infinity

target := mona lisa with dimensions m x n

canvas := random matrix of m x n

best_result := canvas

do

modified_canvas := Copy of canvas with a single random cell inverted

nth_modified_canvas := Run N generations of Game of Life modified_canvas

Compute a score of how close nth_modified_canvas is with target

if score < best_score then

best_score := score

best_result := modified_canvas

canvas := best_result

while(max_iterations limit passed or best_score < threshold)

I hacked up a single core prototype.

def modify(canvas, shape):

x,y = shape

px = int(np.random.uniform(x+1))-1

py = int(np.random.uniform(y+1))-1

canvas[px][py] = not canvas[px][py]

return canvas

def rmse(predictions,targets):

return np.sqrt(np.mean((predictions-targets)**2))

while best_score>limit:

canvases = np.tile(np.copy(best_seed), (batch_size, 1, 1))

rms_errors = []

for canvas in range(len(canvases)):

canvases[canvas] = modify(states[state], (m,n))

rmse_val = rmse(target, nth_generation(np.copy(canvases[canvas])))

rms_errors.append(rmse_val)

lowest = min(rms_errors)

if lowest < best_score:

best_score = lowest

best_result = canvases[rms_errors.index(lowest)]

Hill Climbing works by finding the closest neighboring state to a current state with the least error from a 'target_state' (Mona Lisa). The way I find the closest neighbor in every step is to create a copy of the best solution we have so far and invert a random cell. This change is small enough that we don't risk stepping over any local minima. Also we use root mean square error metric to compare the best state and the target. Other error metrics can be experimented with, but for this problem, I found that RMSE was sufficient.

After a few days of CPU time(!), I was able to obtain something that resembled Mona Lisa after running 4 generations of life.

It was reassuring that my algorithm did indeed work, but I realize I made a bunch of mistakes and of course it's not really scalable for larger images or fast.

Preprocessing

Target Mona Lisa against which our random state was compared with was the medium resolution version taken from Wikipedia and converted to monochrome using PIL's Image.open('target.png').convert('L')

When you're comparing against boolean variables, It's better that we the target as a binary matrix rather than the whole grayscale range.

In this attempt, I simply rounded these grayscale values to 0s and 1s. This was a mistake as it washed away a lot of details.

We could just not round at all and compare against the grayscale version, but there is a better way.

Garden of Eden States

Not every random matrix of 0s and 1s are a valid Game of Life state. States that can never be an nth generation (n>0) of any Cellular Automata are called Garden of Edens. It is almost impossible that our monochrome-rounded Mona Lisa is a valid Game of Life generation. We can only hope to have a solution that's approximately close to the target.

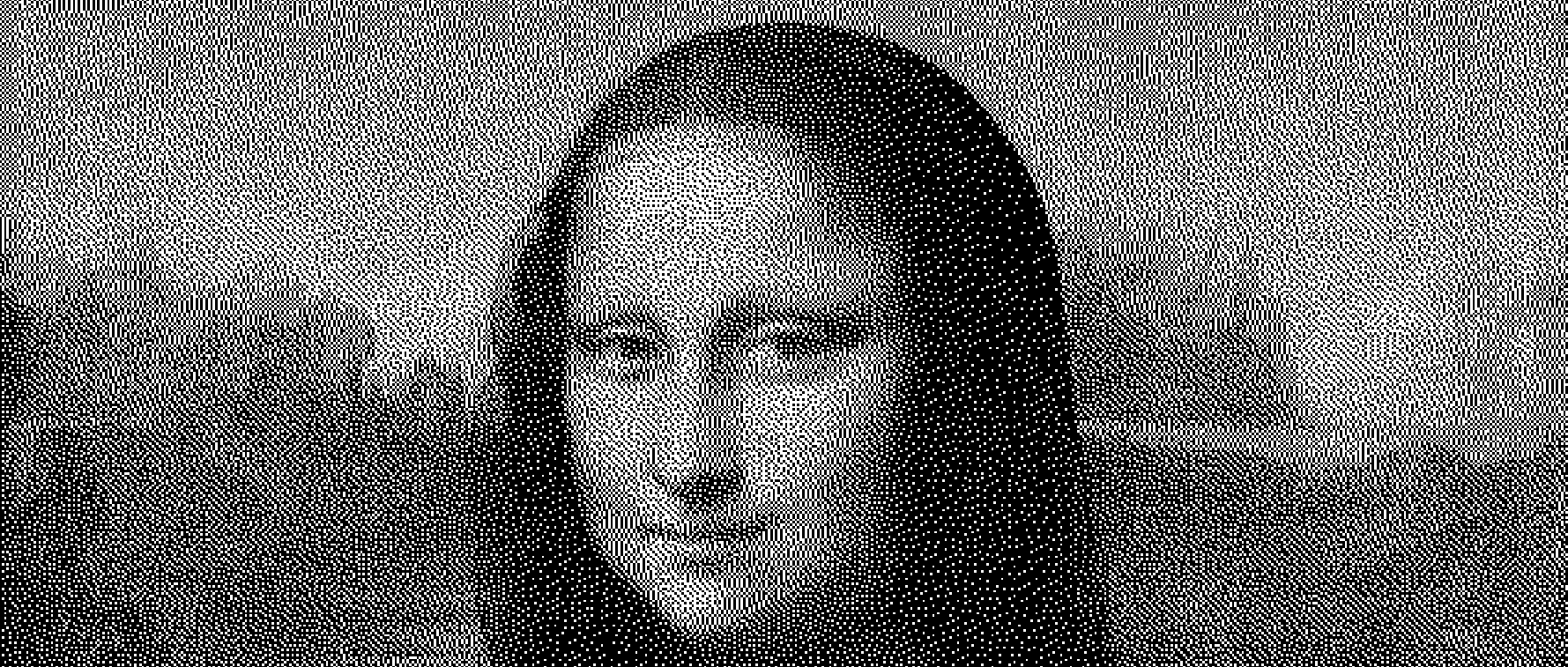

This is a portion of the 4th generation of the state we just prepared.

Judging by the texture, the way life patterns evolve and from just experimenting with images, I found that comparing against a 1-bit dithered version the target should improve the quality of results.

Dithered image has a somewhat even distribution of 0 and 1 cells which is somewhat close to what a randomly initialized Game of Life state will look like after a few generations. This property is also maintained when you scale up the image, (which we'll optimize for soon).

We could do this using PIL (it's Floyd–Steinberg dithering) using Image.open('target.png').convert('1')

Also you can see from the last result, it's impossible to get a continuous array of white cells because they will be killed off by the overpopulation rule. Completely dark areas are stable in life. The end result will be a higher contrast, but slightly darkened version of Mona Lisa. At higher resolutions, this effect is not as apparent.

Vectorization with JAX

The single core unvectorized version is extremely slow. I tried running this in both my 8th gen Core i7 and the Google Colab CPU machines, but you need to wait for hours/days (depending on target resolution) to get something that resembles the original.

Fortunately, This problem is well suited for parallelization.

JAX is a python library that lets you use a version of numpy and compile it to highly vectorized code that can be run on a GPU/TPU. We need to rework this algorithm for a GPU.

GPUs generally suited to high-throughput type computations that has good data-parallelism. We need to exploit the SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data) architecture to gain faster execution speeds.

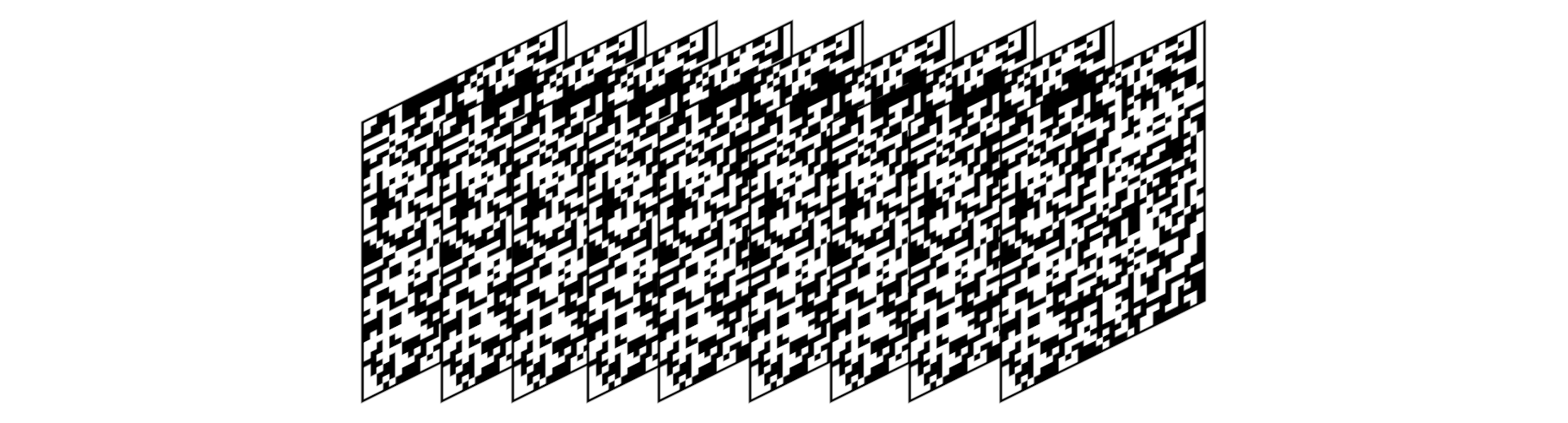

We extrude the target(Mona Lisa) and canvas(initial random state) to 3rd dimension with 3rd dimension being batch_size long tensor loafs.

We set best_canvas to the initial random canvas before our hill climbing loop.

Also, for every loop iteration, we need to produce a random tensor called mutator(same shape as target) with this property: Each slice should have all zeros except a single one place at a random location.

Something like

array([[[1, 0],

[0, 0],

[0, 0]],

[[1, 0],

[0, 0],

[0, 0]],

[[0, 0],

[0, 1],

[0, 0]],

[[0, 1],

[0, 0],

[0, 0]],

[[1, 0],

[0, 0],

[0, 0]]])

Example mutator with shape 5, 3, 2. batch_size being 5

The idea is that in every loop, we use the mutator to calculate the nearest set of neighboring states from our best_canvas like this canvas = (best_canvas + mutator)%2.

We compute N generations of game of life across every slice of this modified canvas. Then, we do a 3D RMSE(mean being calculated for the slice only) on the Nth generation canvas against Mona Lisa, and find the slice with the lowest error. This is slice is then extruded and set to best_canvas and the loop repeats till a finite number of iterations pass.

Code

The notebook for this project is available in github. I'll explain what every block is doing in this section. If you want to see results, skip to the end of the article.

The core of this project, the game of life function is actually taken from this post. Thank you Bojan Nikolic :). I followed his convention of importing jax.numpy as N, jax.lax as L.

%matplotlib inline

import jax

N=jax.numpy

L=jax.lax

from jax.experimental import loops

from jax import ops

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as onp

import time

from PIL import Image

from google.colab import files

Next, wget Mona Lisa

!wget -O target.png https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/Mona_Lisa%2C_by_Leonardo_da_Vinci%2C_from_C2RMF_retouched.jpg/483px-Mona_Lisa%2C_by_Leonardo_da_Vinci%2C_from_C2RMF_retouched.jpg?download

This is not a crazy high res version.It's only 483px wide.

batch_size = 100

image_file = Image.open("target.png")

image_file = image_file.convert('1')

lisa = N.array(image_file, dtype=N.int32)

width,height = lisa.shape

lisa_loaf = onp.repeat(lisa[onp.newaxis, :, :,], batch_size, axis = 0)

This section dithers Mona Lisa using the and extrudes it to batch_size length.

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(42)

canvas_loaf = jax.random.randint(key, (batch_size, width, height), 0, 2, dtype= N.int32) #for tests, initialize random lisa

Here, we're seeding JAX PRNG(will be explained soon). Also we're creating the initial random canvas_loaf with integers 0 and 1.

@jax.jit

def rgen(a):

# This reduction over-counts the neighbours of live cells since it includes the

# central cell itself. Subtract out the array to correct for this.

nghbrs=L.reduce_window(a, 0, L.add, (3,3), (1,1), "SAME")-a

birth=N.logical_and(a==0, nghbrs==3)

underpop=N.logical_and(a==1, nghbrs<2)

overpop=N.logical_and(a==1, nghbrs>3)

death=N.logical_or(underpop, overpop)

na=L.select(birth,

N.ones(a.shape, N.int32),

a)

na=L.select(death,

N.zeros(a.shape, N.int32),

na)

return na

vectorized_rgen = jax.vmap(rgen)

@jax.jit

def nv_rgen(state):

for _ in range(n_generations):

state = vectorized_rgen(state)

return state

Please read B. Nikolc's post for an explanation for rgen function, which runs a single generation of Game of Life.

jax.vmap lets us creates a function which maps an input function over argument axes (vectorize). This lets us run a generation of game of life across every slice in our canvas.

nv_rgen runs N generations of life on our canvas.

Also, @jax.jit python decorator just tells the compiler to jit compile this function. I'm not sure if we there was any improvement in this case as nv_rgen is simply composed of other jitted functions.

def mutate_nj(b, w, h, subkey):

a = jax.random.normal(subkey, (b, w, h))

return (a == a.max(axis=(1,2))[:,None,None]).astype(int)

mutate = jax.jit(mutate_nj, static_argnums=(0,1,2))

mutate_nj(nj = non jitted) generates the mutator tensor we talked about before. It generates this using jax.random.normal and sets max of every slice to 1 and rest to 0. I'll explain the subkey argument soon.

We jit this function as mutate. Additionally, we need to mark b,w,h arguments as static so that the compiler knows they're constant throughout the execution.

def rmse_nj(original, canvas, b, w, h):

return N.sqrt(N.mean(L.reshape((original-canvas)**2,(b,w*h)) , axis=1))

rmse = jax.jit(rmse_nj, static_argnums=(2,3,4))

rmse is pretty self explanatory. The only major change from the CPU version is that we compute mean across 1st axis (loaf's long axis).

def hill_climb(original, canvas, prng_key, iterations):

with loops.Scope() as s:

s.best_score = N.inf

s.best_canvas = canvas

s.canvas = canvas

s.prng_key = prng_key

for run in s.range(iterations):

s.prng_key, subkey = jax.random.split(s.prng_key)

s.canvas+=modify(batch_size, width, height, subkey)

s.canvas%=2

rmse_vals = rmse(original, nv_rgen( s.canvas ), batch_size, width, height)

curr_min = N.min(rmse_vals)

for _ in s.cond_range(curr_min < s.best_score):

s.best_score = curr_min

s.best_canvas = N.repeat((s.canvas[N.argmin(rmse_vals)])[N.newaxis, :, :,], batch_size, axis = 0)

s.canvas = s.best_canvas

return s.canvas

hill_climb is the main function in the program. It is one big JAX loop construct. We could use standard python loops here, but we need to take full advantage of using JAX.

JAX loops (jax.experimental.loops for now) is a syntactic sugar functions like lax.fori_loop_ and lax.cond. lax loops(actual XLA loops) that have more than a few statements and nesting gets very complicated. JAX (Experimental) loops however bring it somehwat close to standard python loops. The only caveat is that the loop state, ie. anything that mutates across interations have to be stored as a scope member. For us, this includes the best_score, best_canvas, temporary canvas where we run life and the PRNG key.

JAX PRNGS

Numpy uses a managed PRNG for all of it's functions having random. ie, seeding it and managing it's state are entirely managed by numpy. As I understand, in parallel executions(like in a GPU) and in situation that need a large number of randoms, this method has flaws. It is difficult to ensure that we have enough entropy for producing large enough quantity randoms.

Unlike numpy, JAX random generation is "unmanaged". Every jax.random function needs the current state of the PRNG as it's first argument, and every time we execute one of these functions, the PRNG state has to be updated using jax.random.split.

Not updating the PRNG state will quickly result in the same set of randoms over and over again. I did'nt quite understand this part the first time I wrote the loop, and it resulted in the algorithm ceasing to find new variations of canvas states. This happened becasue we're generating the same mutator tensor over and over again.

Splitting PRNG state is also the way to ensure that every parallel component of the algorithm generate distinct randoms. Find more details of JAX PRNG Design here

cond_range

Why are conditionals also loops in JAX? er.. I'm not quite sure about this. It should be possible for cond_range to output a regular boolean instead of a 0/1-long iterator. But for some reason, it's build like that.

If we found a better canvas slice, we extrude that and set it as our best_canvas and it's score as the best_score.

After a finite number of iterations, we'd obtain a Game of Life state that reveals a Mona Lisa after N generations.

Results

Running \~1000 iterations for a 483px wide Mona Lisa on the google colab GPU runtime only takes around 40 seconds!. Compared to the CPU version which takes several hours to do the same for a smaller image, I think we've achieved our goals.

A life state with the highest similarity to the target is achieved after running for \~23000 iterations (10 minutes). After 23K, the gains start to diminish greatly and doesn't seem to improve much, even if you run for 100K iterations.

Also, Images targetted at lower generations tend to have better fit as expected.

Conclusion

I was really looking for an excuse to dive into JAX that doesn't necessarily involve it's automatic differentiation capabilities. JAX can be used to any general computing problem that works on tensors. I'm sure I made many mistakes here, but this was very much a learning experience for me.

Thank you Kevin Galligan for the original idea and Bojan Nikolic for the Game of Life snippet.